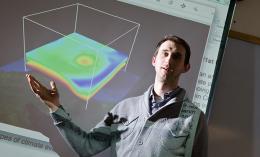

Toby Ault

Testing climate models to make them better

When Toby Ault was a senior at the University of Puget Sound back in 2002 he was nominated for a Watson Fellowship. “I was a math major and a Spanish minor and I was not exactly sure what I wanted to do with my life,” says Ault, 14 years later from his office at Cornell University. “I won a Watson Fellowship and used it to travel for a year in Charles Darwin’s footsteps.”

The way Ault tells the story of that year, a listener can feel the momentum building toward an inevitable conclusion. First, he tells about heavy rains and flooding in Uruguay. The locals all told him it was because of El Niño. (El Nino is the name given to a periodic abnormal warming of the surface waters of the Eastern Pacific Ocean.) Then, six months later and half a world away in the Outback of Australia, Ault stopped to help a rancher whose tire had blown out. The rancher invited him home for dinner and told Ault about the drought and how it was forcing him to sell off much of his herd. The rancher said the drought was a result of El Niño. Then, a few months later, Ault was half a world away in England, visiting Darwin’s home in Shrewsbury. On that particular day, England experienced its highest temperature ever recorded. Later that week, Ault went to the London Natural History Museum and heard a talk by an oceanographer, who was speaking about global climate and how it changes over time. “It all just hit me,” says Ault. “I saw all at once what I wanted to do. I wanted to apply math to climate science and see what I could discover.”

Flash forward to 2015. Toby Ault is now an assistant professor at Cornell’s Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences (EAS). Instead of simply hearing about El Niño, he studies it as part of his effort to diagnose current models of the global climate system in an effort to make them better. “One key to improving current models,” says Ault, “is to disentangle natural influences on climate from forced external influences.” Ault has chosen to focus much of his work on the southwestern corner of the United States. “The Southwest is a great place to develop my ideas and methodology,” says Ault. “There is a long record of climate data stored in the tree rings and the area is prone to naturally occurring periods of drought. It is certainly vulnerable to El Niño’s counterpart, La Niña, (which is the cool phase of this oscillation.)”

In order to look forward and see what Earth’s climate might be like in the near future, Ault is first looking back 1000 years. The long, reliable record of climate data stored in tree rings of the Southwest, (combined, of course, with many other factors), allows Ault to test current models of how the climate works. The better a model can describe what has already happened, the more confidence he and other researchers can have in its predictive ability. “Models that simulate past fluctuations accurately,” says Ault, “might therefore give us better insight into likely future climates.”

By looking at the last thousand years, Ault wants to get a clear idea of the natural variability in the climate and the role factors like solar output, volcanic eruptions, and greenhouse gas concentrations play. In this way he can understand the baseline and start to create a reliable measure of the variability caused by human activities in the past two hundred years. “The models we have today,” says Ault, “don’t consistently explain what we find in the climate record of the Southwest. The big picture is fairly clear, but the smaller scale, local effects are not very well explained by the current models.”

Ault is careful to point out that his goal is more than simply improving current models of how the global climate system works. “My time scale is in the ten-days to ten years-range—my focus is more immediate and more regional,” says Ault. Since Ault joined the field after his year following in the footsteps of Charles Darwin, the field has evolved considerably. Ault says the chief improvement in climate models comes from better computing power, which allows for a greater faithfulness to small-scale features. “As I said, the big picture is fairly clear. What I want to do is to better predict the local short-term effects of climate change that are not at all clear right now. The impacts of the work climate scientists do are so consequential that it is essential that we get it right.”

Part of the reason Ault joined the faculty at EAS is the overall optimistic atmosphere he found in the department. “People here are doing good research with the goal of making things better,” says Ault. “Everyone here believes that we can and will develop the tools and build the technologies that will help the world respond to climate change in a way that will make people’s lives better.” When pushed a bit on the negative effects of climate change, Ault responds, “The evidence I see of past mega-droughts in the Southwest comes from trees—trees that survived the droughts. This gives me hope for our capabilities and for the future.”