Two centuries ago, menopause wasn’t much of a concern, mainly because most women didn’t live long enough to experience it. Now, with lifespans reaching well into the 80s, this transition is a major inflection point in women’s health, linked to everything from osteoporosis to Alzheimer’s. Yet, despite its significance, menopause remains poorly understood.

At Cornell, a pioneering group of researchers is stepping into that gap, using cutting-edge technology and interdisciplinary expertise to change how we understand, treat and support women through this transformative phase of life.

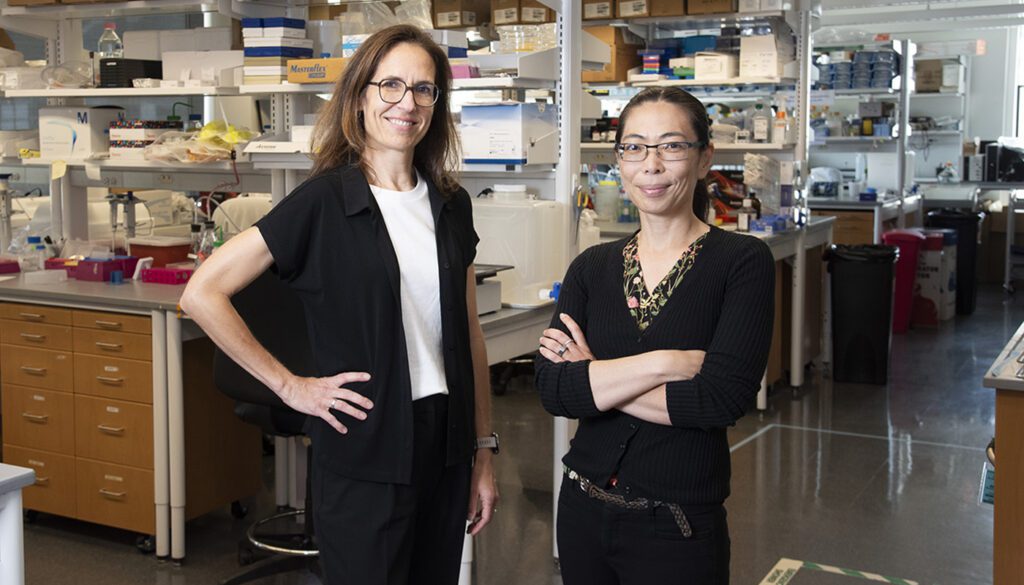

A growing consortium of faculty across Cornell’s Ithaca campus and Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City are forming Menopause Health Engineering, a new research initiative to tackle unanswered questions around menopause and its links to aging-related diseases. The inaugural team spans nine faculty members across four departments, and includes expertise in engineering, biomedical science, and medicine. The core group of faculty within Cornell’s Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering said they are excited to broaden their membership and are looking to partner with other academic labs or industry as they develop these new research directions.

Redefining aging research through women’s health

Why menopause? Claudia Fischbach-Teschl, the James M. and Marsha McCormick Family Director of the Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering and Stanley Bryer 1946 Professor of Biomedical Engineering explains: “Menopause affects 50% of the population. And when you look at the development of menopause, you’re not going from the full spectrum of hormones to no hormones. It’s phases that people refer to as perimenopause and then menopause, which together are affecting women for the majority of their life.”

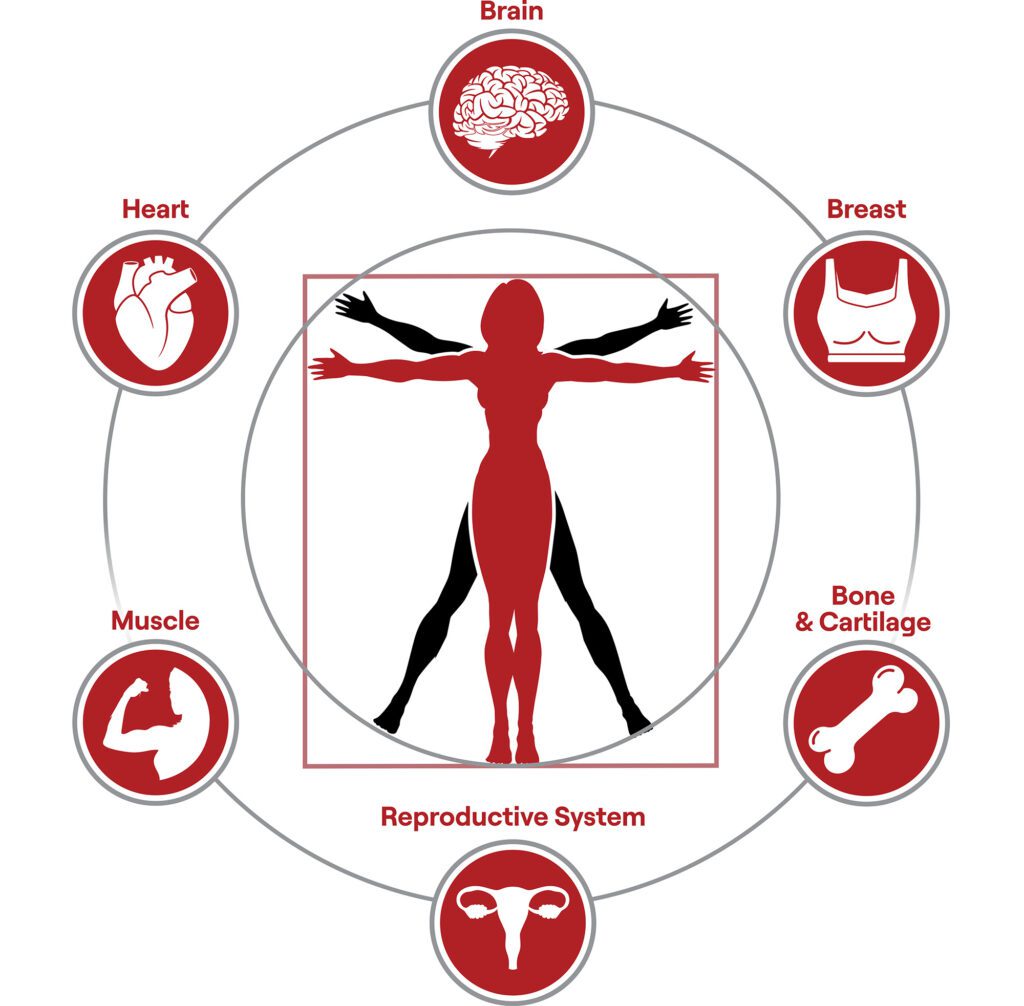

And that transition is far from easy. “All kinds of conditions develop as women undergo this transition to menopause,” says Fischbach-Teschl, “including cardiovascular disease, cancer, osteoporosis, dementia and metabolic diseases.”

While many of these conditions are traditionally labeled as aging-related diseases, Fischbach-Teschl underscores that there are deeper, sex-specific factors at play. “These so-called aging diseases are affecting women very differently than men,” she says, “and yet we understand very little about how women are affected in this stage of their life.”

One major contributor to that knowledge gap is a long-standing bias towards using male subjects in biomedical research and clinical trials. For example, using male animals for obesity research is faster as male mice gain weight more quickly. Also, male animals are often cheaper than females, which has led to gaps in understanding of female biology, aging and disease.

Nozomi Nishimura, founder of the initiative and associate professor in the Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering, reflects on her own learning curve: “I’ve been working on diseases of aging for over a decade, such as Alzheimer’s disease and cardiovascular disease. We’ve always had males and females in our experimental groups. It never really occurred to me, and was a hole in my education, that when we’re talking about diseases of aging, we should really be looking at and considering something like menopause.”

She adds, “At Cornell we have really strong researchers for diseases of aging. We have a powerful engineering and tool-building culture that sets us at an advantage. In terms of women’s health and menopause, we have an opportunity and a need and a unique niche that we can address.”

That niche is also rich with potential for innovation. While there is a societal responsibility to understand women’s health, Menopause Health Engineering also targets untapped economic potential within an accelerating market. Currently, only about 2% of health sector private investment is directed toward women-specific health needs. New research into menopause and disease in women could catalyze significant advances in biomedical technology and clinical care.

“We want to propose and develop novel therapies that actually address symptoms,” Nishimura says, “not just suggesting turning on a fan for hot flashes.”

“If we understand better how women function relative to men, that eventually also has a benefit for the men,” adds Fischbach-Teschl, “because then their conditions are better understood. It basically will make research and medicine more personalized.”

As we age, diseases are often deeply interconnected. Osteoporosis, for example, is tied not only to bone health, but also muscle and metabolic health. It also plays a significant role in breast cancer risk and progression. None of these organs, systems or diseases function in isolation, and so research must adapt. Understanding intertwined problems like multi-organ diseases requires the type of interdisciplinary team that can be found at Cornell.

Innovating at the intersection of engineering and biology

Menopause is more than a biological transition – it’s a technological challenge.

“You need technology in order to understand, diagnose and treat changes that are imposed by menopause,” Fischbach-Teschl says. “Some examples include imaging to observe cells in real time, biomedical devices to measure different physiological signals, and body-on-a-chip systems that can mimic how cells behave in a human’s body. There is also a need for advanced computation, because with a large data set, you need to figure out how to use the data to inform therapies or other experiments. Finally, there is usually some sort of innovation and technology needed to translate your findings into changes in clinical care or therapy.”

The Menopause Health Engineering initiative aims to have faculty across departments contribute their technological and biological expertise to bridge the most complex questions in menopause and women’s health.

Beyond the lab, faculty are equally committed to student engagement. The team plans to integrate their research with student experiences, embedding menopause and women’s health questions into senior design projects and clinical immersion terms at Weill Cornell Medicine. “There are great opportunities to leverage current programs and to incorporate the menopause and women’s health focus,” Fischbach-Teschl says.

The team is also drawing inspiration from nature. Remarkably, only a few species undergo menopause, including humans and orcas. “Orcas, killer whales, are similar to humans, with a long lifespan,” Nishimura notes. “After menopause, orca matriarchs actually become the leaders of their whale pods.”

That biological reality carries a cultural message. “It’s an opportunity for women to think about this time as a transition point in life where you’re not having children anymore, and we have many, many years left,” says Nishimura. “Those are actually the years that are our prime for leadership.”

Looking ahead, Nishimura and Fischbach-Teschl envision a wide-reaching network of engineers, biologists and physicians collaborating across departments and campuses. They plan to investigate menopause through animal models, tissue-engineered systems and clinical data, bringing together cutting-edge science and technology with real-world health needs.

To sustain this momentum, the faculty are actively pursuing large grants to support the group’s collaborative research efforts. At the same time, smaller, innovative initiatives – such as joint fellowships that pair trainees from different labs – will help grow the initiative from the ground up.

“Faculty are already meeting regularly to discuss findings, build collaborations and shape the future of menopause research,” says Nishimura. Their goal is not only to fill critical scientific gaps, but also to redefine how women’s health is understood, prioritized, taught and advanced for generations to come.

Initial faculty and advisor-partners

The Menopause Health Engineering initiative will engage with expertise from across the university and its affiliate institutions to enhance knowledge of women’s health and diseases later in life and leverage this knowledge to create innovative engineering solutions aimed at improving health and longevity. Current advisor-partners can be found on the Menopause Health Engineering initiative website.