News

-

![]()

3D-printed superconductor achieves record performance

Nearly a decade after they first demonstrated that soft materials could guide the formation of superconductors, Cornell researchers have achieved a one-step, 3D printing method that produces superconductors with record properties.

-

![]()

Biodegradable ‘heat bombs’ safely target specific cells

Cornell researchers developed a new way to safely heat up specific areas inside the body by using biodegradable polymers that contain tiny water pockets, a technology that could lead to precise and noninvasive diagnostics and therapeutics.

-

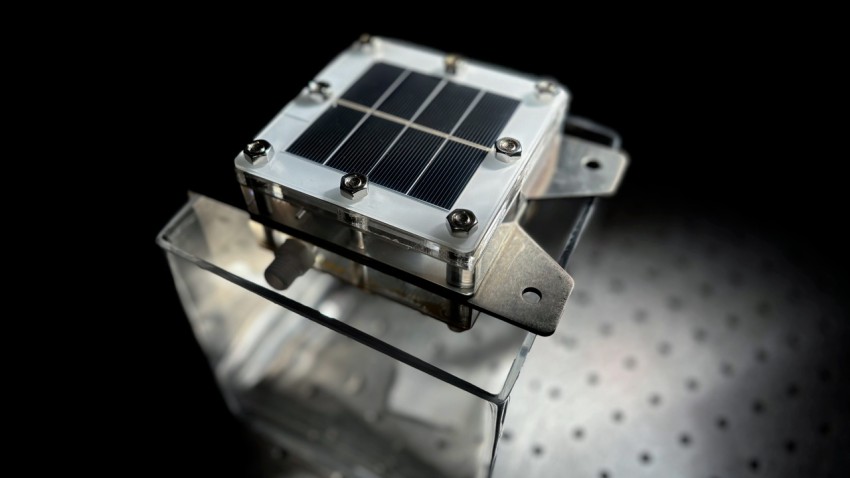

![A Cornell-led team built a 10 centimeter by 10 centimeter prototype device that produces carbon-free “green” hydrogen via solar-powered electrolysis of seawater, with an important byproduct: potable water.]()

Sunlight and seawater lead to low-cost green hydrogen, clean water

Researchers developed a low-cost method to produce carbon-free “green” hydrogen via solar-powered electrolysis of seawater, with a helpful byproduct: potable water.

Latest Awards and Recognition

View all-

Three research teams receive grants

Three Cornell engineering research teams have been chosen as recipients of AI and Climate Fast…

December 1, 2025

-

Barcheck, Culberg earn NSF award for field study

Grace Barcheck, assistant professor, and Riley Culberg, assistant professor, have received an award from the…

November 25, 2025

-

Trio named Engaged Faculty Fellows

Three Cornell Engineering faculty members are part of the 2025-26 Engaged Faculty Fellows cohort.

November 24, 2025

-

You paper featured on Chemical Science cover

Fengqi You, the Roxanne E. and Michael J. Zak Professor in Energy Systems Engineering, had…

November 17, 2025