10-9-8-7-6…

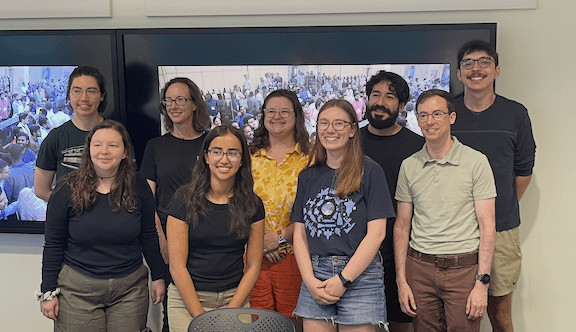

A group of nine faculty members and graduate students met in the Map Room of Snee Hall early-ish on the morning of July 30, 2025. Rowena Lohman, professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, organized the gathering and provided a continental breakfast the equal of any Best Western or Quality Inn. However, people were not there for the bagels and orange juice – at least not entirely.

They were there to watch a livestream of a rocket launch from Satish Dhawan Space Center in Sriharikota, India. The professors and graduate students in Snee Hall had a special interest in the payload of this particular rocket, and there was some anxiety in the air. The rocket was carrying the NASA-ISRO SAR satellite to its orbit and there was a lot riding on a safe lift-off, uneventful climb and successful separation.

Everyone in the room was sitting, except for Lohman.

She stood off to one side, fidgeting a bit, eyes trained on the screen, occasionally identifying colleagues who had made the trip to India to be present for the launch as they appeared on-screen and the countdown clock ticked away the minutes and seconds.

Many years in the works

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) technology has been around for a long time. It was invented in 1951 by engineer and mathematician Carl Wiley and was developed over the next decade by Wiley and others with military uses in mind. Fairly soon after its development, SAR began to be applied to the broad field of planetary science. In the early years of SAR, the systems were limited to high-flying aircraft.

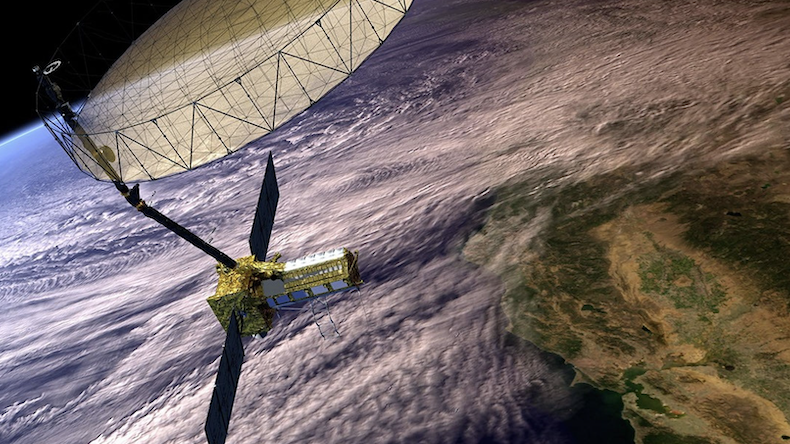

In 1974, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory collaborated to develop SAR technology for use on a satellite so they could make oceanic observations. Their work resulted in the 1978 launch of the Seasat satellite, which put a SAR system in orbit. There have been many SAR satellites launched since Seasat, with the technology improving steadily and offering high-resolution imaging capabilities for various applications. These include environmental monitoring, disaster response, defense and intelligence, infrastructure monitoring, maritime surveillance and geophysical research.

When geophysicists want to measure elevation changes on the Earth’s surface, one source of data is orbiting SAR satellites. Researchers from Cornell have a long history of involvement in the design of these radar tools. In the 1980s geology professors Art Bloom and Bryan Isaacs worked on earlier proposals that eventually led to this mission. Today, Cornell alumni Rick Forster, Ph.D. ’97, and Eric Fielding, Ph.D. ’89, are on the science team of the NISAR mission.

The mission enabled by July’s launch in India is called NISAR and it has been in development since 2014, when NASA and the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) signed an agreement to collaborate on a joint dual-frequency radar mission using SAR technology.

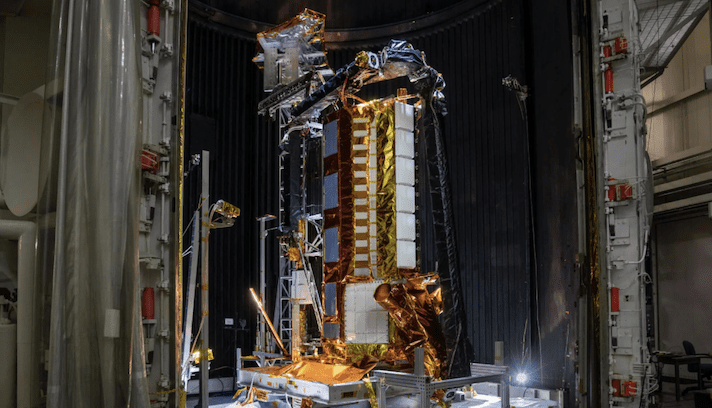

The signed agreement called for NASA to develop one frequency of the synthetic aperture radar while ISRO developed the other frequency. ISRO was also responsible for building the satellite bus, (which is the main structural component of the system and holds all of the equipment), building the launch vehicle and lifting it all into orbit.

NISAR is the first radar imaging satellite to employ dual frequencies operationally on a science mission and, if successful, it will track small movements across almost all of Earth’s land and ice surfaces. Incredibly, it will be capable of measuring movements as small as a centimeter from its orbit more than 450 miles above the Earth. NASA has described NISAR as the most advanced radar system it has ever launched.

We have liftoff

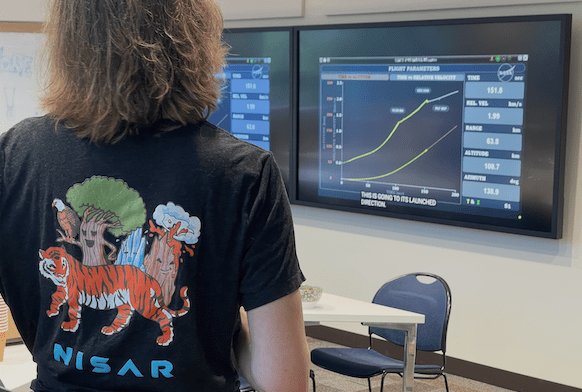

In the hour between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time on July 30 the rocket fired its engines, lifted away from the tower, and accelerated up through Earth’s atmosphere. Through the entire process, the tension in the Snee Hall Map Room was palpable. The payload at the top of the rocket represented thousands of hours and billions of dollars of time and effort. For many scientists on hand in India for the launch or watching remotely, like the group at Cornell, it also represented the primary tool they will use to gather the data they need for their research to continue.

All phases of launch day were successful and 18 minutes after lifting off from Sriharikota the NISAR satellite separated from the rocket it had caught a ride on without a hitch.

Lohman was equal parts relieved and thrilled. She has been part of the NISAR project from the early days of the collaboration and had a lot invested in its success. She served on study groups for earlier incarnations of the NISAR mission since 2008 and has been the lead for soil moisture since 2019. “We have all seen video of rockets exploding on the launch pad. We’ve all heard of satellites that didn’t deploy properly. This is very complicated stuff and there is no room for error,” Lohman said. “If something had gone wrong, it would have been devastating.”

On Aug. 15, NISAR deployed its 39-foot radar antenna reflector. Since then, it performed various orbital maneuvers that have brought it to its current “science orbit,” which allows it to scan nearly all of the planet’s land and ice surfaces twice every 12 days. NASA expects NISAR to start sending science-quality data back to Earth in late-October or early-November.

How are we going to deal with all this data?

In addition to its dual-frequency radars, another feature that sets NISAR apart from all previous SAR satellites is the amount of money NASA has invested in the data “pipeline” from the satellite back to researchers on the ground.

“Many of the satellites that are up there are turned off a lot of the time, to save power, and because it is expensive to get the data to the ground,” Lohman said. “The big change with NISAR has been that NASA really invested in the capacity to acquire and send as much data as possible. We’re going to have petabytes of data coming from the satellite, and NASA has committed to make this available to everyone so that we can get the most value for what has been invested in this satellite.”

Large volumes of data come with new types of noise and other challenges. Lohman has worked for years with data collected by Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar and knows a few things about working with enormous amounts of data. She has gotten good at creating techniques to take some of the noise out of the data and make them more useable. It is not a stretch to imagine she and her students will do the same with the data collected by NISAR.

NISAR is the first of its kind in terms of spatial coverage, temporal sampling and the diversity of microwave frequencies. Researchers with various specialties will consume the data collected by NISAR in different ways. Lohman will be focused on changes in brightness over time in the images created by NISAR. Using its L-band radar system, NISAR will provide high-resolution surface maps. And because wetter soils reflect more radar signals back than drier surfaces do, areas with greater soil moisture will appear brighter in the images.

Knowing how much moisture is in the soil in a given place at a given time can be enormously helpful. Additionally, knowing how soil moisture content changes over time is essential information for many applications. This data can help weather forecasters, climate modelers, farmers, water resource managers, and the people tasked with responding to flood and drought disasters.

In addition to supporting water resource management, climate science and agriculture, NISAR could provide early warning of impending landslides and volcanic eruptions, measure ice accumulation or loss on icesheets and glaciers, and “see” through clouds during hurricanes to reveal the extent of flooding and identify areas needing help. It will also allow for the first time almost complete coverage of Antarctica, augmenting the valuable, but hard-won data that researchers can collect in the field. Now that the launch, deployment and positioning of NISAR have all gone smoothly, Lohman and her graduate students can breathe a sigh of relief, turn on their computers, roll up their metaphorical sleeves and get busy processing data. The NISAR mission is scheduled to last three years, though it could continue beyond that if funding is found to support its management. The first science-quality data have not come in yet, but it is already a pretty safe bet that Lohman will be among those lobbying for that extension.